The Internalised Autistic Experience

External and Internal Autistic Experiences

As we have shared, autistic people experience, process and express the world in different ways. These differences are not fixed traits or “types”, and can shift depending on the environment, sensory load, stress levels and how safe a person feels to be themselves.

In our community, people sometimes use the phrases internal autistic experience and external autistic experience to describe these differences. These terms can be useful starting points, but they are a simplification. What is visible or less visible can shift depending on the environment, sensory load, expectations and how safe a student feels to be themselves. This is not about two types of autistic people. It is about recognising that some autistic experiences and needs are easier to notice, while others can be harder to see.

At times, someone’s experiences may be more externalised or visible, for example movement differences, clear signs of overwhelm or communication differences. Because these are easier to observe, they are more commonly recognised within traditional understandings of autism. For some, these external expressions are a consistent part of how they move through the world (including those who have ongoing high support needs or co-occurring conditions), rather than something that changes with context.

Other experiences can be harder to see. A student’s nervous system may be working very hard to stay regulated, while their distress is internalised rather than visible. This might look like staying quiet, withdrawing, scripting or masking discomfort. The internal experience is real, but can be missed when others only look for external signs.

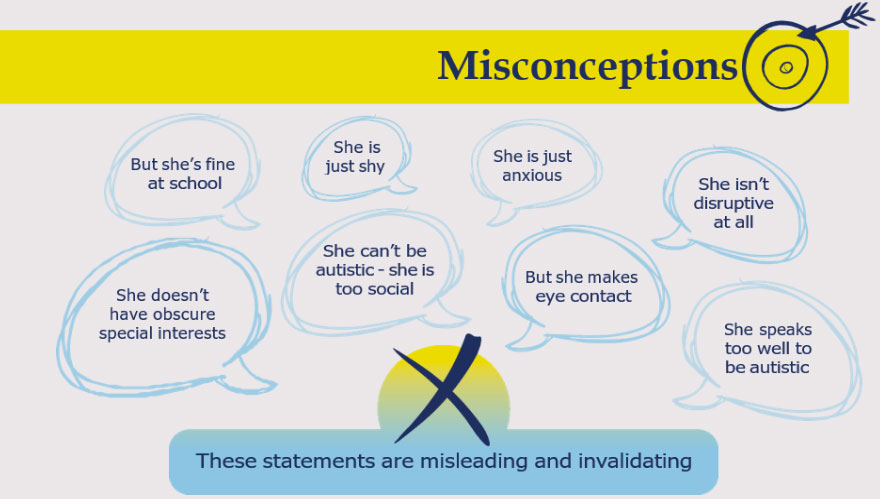

These less visible experiences can be present for autistic people of any gender. However, girls and gender-diverse young people (among other factors) are often socialised to “fit in” or not take up space, they may be more likely to internalise and mask their autistic needs in certain environments.

Many autistic girls and autistic gender-diverse students develop internalised coping strategies in environments where there is pressure to appear “fine”. This reflects social expectations and learned survival responses, rather than differences in autism itself. These patterns are not fixed and can vary across contexts and change over time.

Because some autistic experiences are less visible, we cannot assume that a student is coping based on how they appear. Support should not depend on a student being able to explain or show what they need. Instead, we need to notice patterns over time, stay curious, and create environments where needs can be recognised and met without the student having to explain or mask.